Some of the day went to catching up and playing disc golf, while the rest was spent tuning my bike and picking up supplies for the road ahead.

Part of a 4-post adventure — jump to any post: Bikepacking – Week 1 | Bikepacking – Week 2 | Bikepacking – Week 3 | 3-Day Hike of Kebnekaise

The morning of departure arrived before I knew it. Aside from the lingering soreness in my legs, I felt almost as fresh as when I started the trip two weeks earlier. The long-overdue reunion with my friend had been a joy, and I realized how quickly I had grown used to modern comforts. That made me feel a little hesitant about continuing to ride on the bike and live in the wilderness.

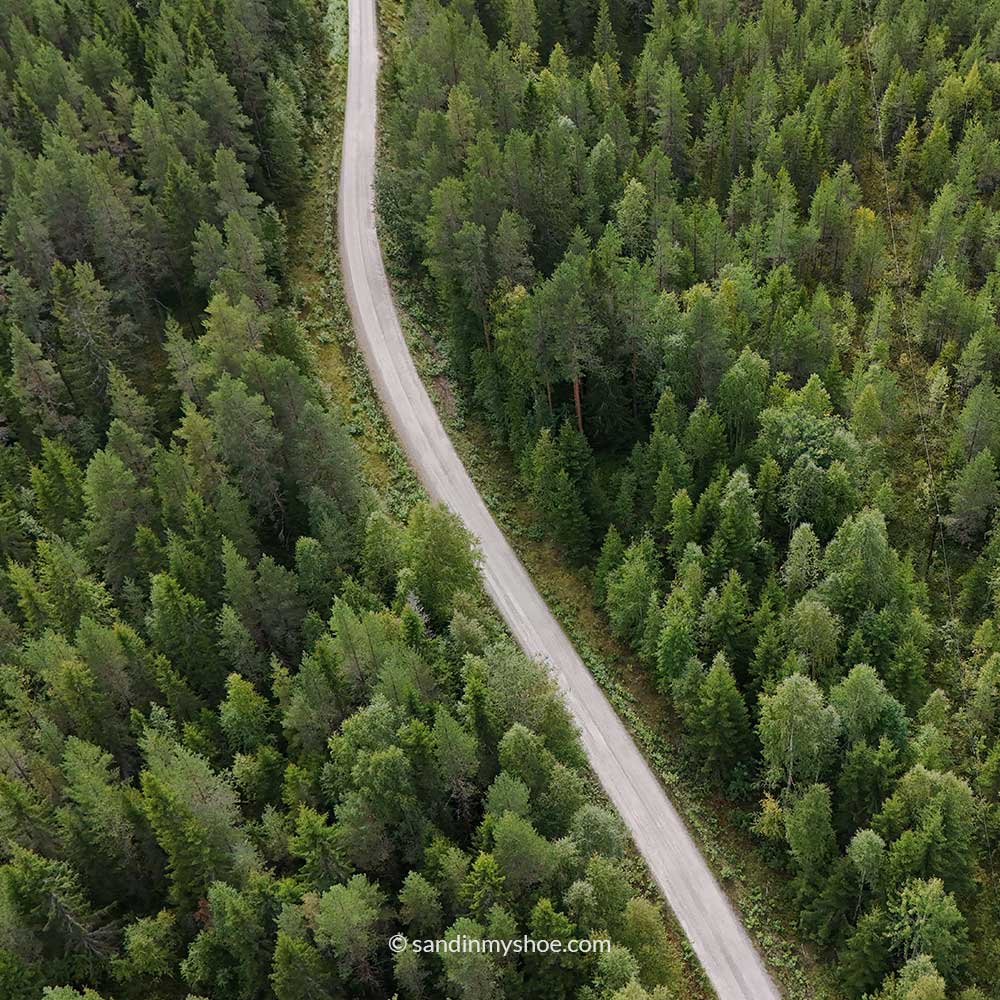

But within just a few kilometers, with the sun on my skin and the fresh wind in my face, I remembered why I was doing this. The sense of freedom returned, and with it the joy of being in nature and traveling at a slow pace. As blood rushed to my legs, the soreness faded and I was ready for the last week of cycling before turning toward the mountains. Unfortunately, halfway through the day, I crashed my drone and could no longer take any aerial footage.

Reading the Habits of the Northerners

I kept riding along the coastline, with about a hundred kilometers left before the route turned inland toward true Lappland. The farther north I went, the more I began to notice the small habits that set the northern Swedes apart.

The most obvious sign was the abundance of surströmming—the infamous fermented herring—advertised in nearly every grocery store. The selection was surprisingly wide, with many local producers and plenty of people who seemed fiercely loyal to their favorite brand. It’s a sight you rarely encounter in central or southern Sweden, where people mostly buy it as a prank gift.

Another sign revealed itself in the way people spoke. Northerners talk at a slower pace, and they have a peculiar way of saying yes. Instead of a nod, the lips are gently pushed forward in a circular shape, and air is sharply inhaled. That sound means yes. And yes… it takes some getting used to.

According to my friend Daniel, there’s an even subtler version—done without the intake of air. You simply pout your lips slightly upward, a stealthy “yes” that can easily be mistaken for a strange kiss. For outsiders, it’s confusing and potentially misleading. It’s best reserved for people who’ve lived here for generations and know the art of the silent affirmation.

Then there’s the local music genre: Epadunk. It’s the soundtrack of northern teenagers, blasted from their A-tractors—cars legally limited to 40 km/h. A Volvo 240 or 740 is usually the vehicle of choice.

The genre itself is a chaotic mix of EDM, eurodance, and crude humor, with lyrics about alcohol, sex, A-tractors, and countryside romance. Some nights, as I lay in my tent, I could hear it faintly thumping in the distance; other nights, it rumbled closer along a nearby road—reminding me that I was deep into the north and that a party can happen anywhere, as long as you have a reliable Volvo and a taste for bad music.

I’d heard about these northern quirks before, but nothing prepared me for what I found on a quiet, beautiful beach one afternoon. While exploring, I came across a public outdoor bathroom—already a small blessing in itself for someone staying in a tent. But when I opened the door, I froze. Inside were two toilet seats, side by side. Never in my life had I seen a Swedish bathroom like this.

Of all the oddities the northerners come up with, this one truly took the prize. Maybe it’s a symbol of northern romance—a place for extreme handholding, perhaps? Who knows. Maybe they even practice tandem-wiping to the beat of Epadunk, sealing their eternal love bond in the most unholy of ways.

Anyway, I wasn’t there to judge. I just enjoyed witnessing the oddity.

True Lappland: Reindeer and Arctic Remoteness

I had been riding along the coast for roughly 700 kilometers, and after Piteå it was finally time to head inland—toward true Lappland. My first stop was Boden, followed by a long stretch of Arctic remoteness with sparsely populated areas. I’d been advised to carry at least two days’ worth of food, just in case something happened or I didn’t make it to the only grocery store during its limited opening hours. From Boden to Gällivare, it’s about 190 kilometers. For a fast, lightweight cyclist, that might be a day’s ride, but for me—looking more like a minivan on two wheels—it was at least two.

After that, it was about 130 kilometers to Kiruna—the last stop for groceries before the mountain, which was another 70 kilometers away.

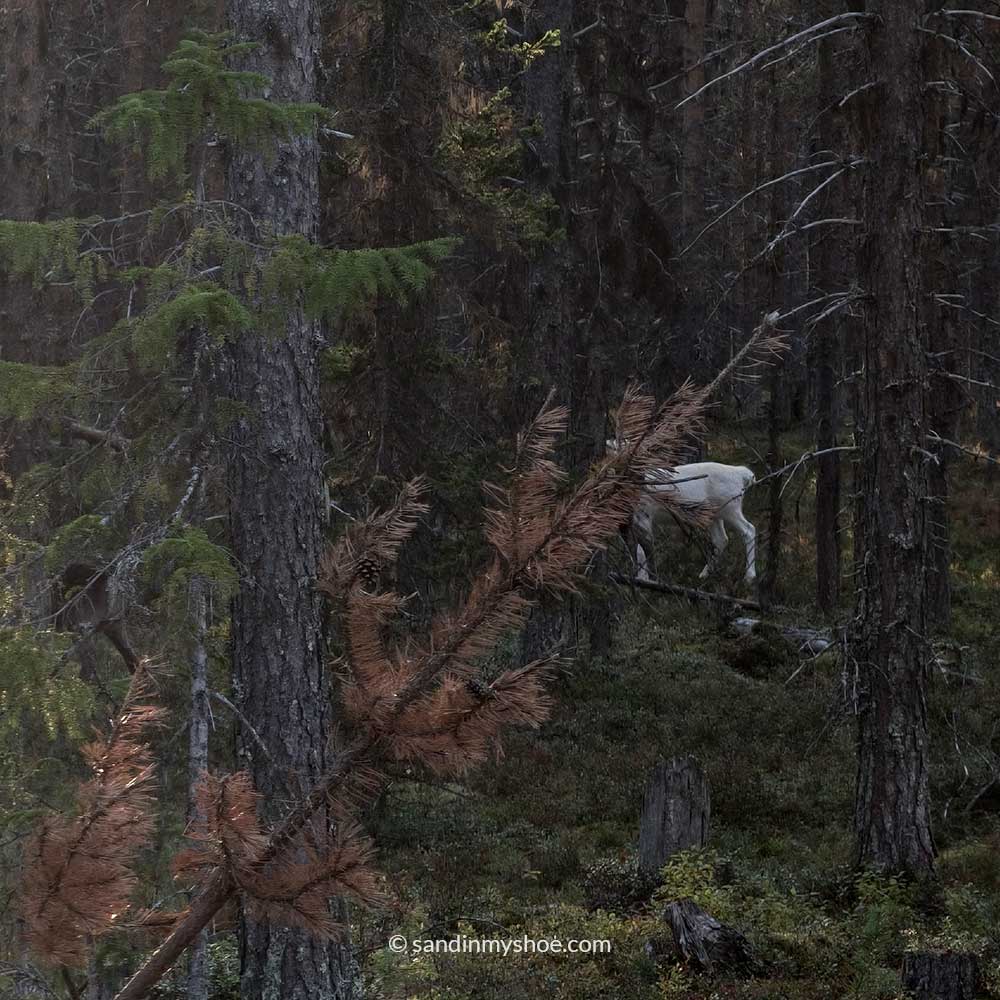

Riding through this quiet stretch felt incredible. The road wound through dense forest, with signs warning of military training grounds and hunting zones. Even the occasional sound of gunfire soon faded into the background. The landscape was wild and untouched—serene rivers with water so fresh you could drink it straight from the stream, and roads so empty that some days I met more reindeer than cars. I even saw an albino one. Each time a reindeer appeared on the road, it froze and stared at me until I reached for my camera—then bolted off like a naked celebrity fleeing the paparazzi.

One evening, after finishing my ride for the day, I bathed under a bridge like a troll in a cool Arctic river—completely naked washing myself and my clothes, without a care in the world. The solitude of the north felt liberating. Being alone in that vast landscape made me understand why so many tourists come here just for the nature.

The next day, I managed to reach the only grocery store between Boden and Kiruna while it was still open. To my surprise, a German man was working there. After chatting for a while, I learned that many Germans and Dutch fall so deeply in love with northern Sweden that they occasionally move here permanently. I guess the grass really is greener on the other side—probably literally in this case.

After stocking up on food for the road, I continued pedaling toward Gällivare, about 55 kilometers away, with another 125 kilometers still to Kiruna. Somewhere along the way, I came across what must be one of the smallest fire stations in the world—a tiny red garage barely big enough to store a hose. I guessed the town budget was a bit tight in such a sparsely populated area.

Also, a day before reaching Kiruna, I found a pizzeria in a small mining town. I was on the hunt for as many calories as possible and ordered yet another audacious pizza: a meat pizza topped with fries—another invention that would earn you enemies if attempted anywhere near Italy.

Kiruna: The City on the Move

The city of Kiruna was moving, much like myself. Massive parts of it are being relocated because of expanding mining operations. Even the church was moved—at a cost of SEK 500 million (~$50 million), all paid by the mining company. Although residents are compensated, many aren’t happy. Entire neighborhoods filled with memories are being erased.

When I arrived, I had a few objectives: buy a large hiking backpack that could carry a lot, stock up on food for five days for the hike plus the trip to the mountain and back, and charge all my electronics.

As someone who likes to compare every option before buying, I did the same with the backpack. I spent far too long comparing every backpack in town, determined to find the best one for the best price—all while traveling by bicycle. By the time I made my choice, I still had to buy food and recharge my gear at McDonald’s. When I finished, it was dark and pouring rain.

That left me searching for a camping spot in the downpour, and to make things worse, I realized my brakes weren’t working properly. Desperate, I found a small clearing next to a jogging path in the forest and pitched my tent there. Early the next morning, I was woken by a group of teenagers on their school gym class run, who asked me what on earth I was doing there.

I quickly packed up and continued toward Nikkaluokta.

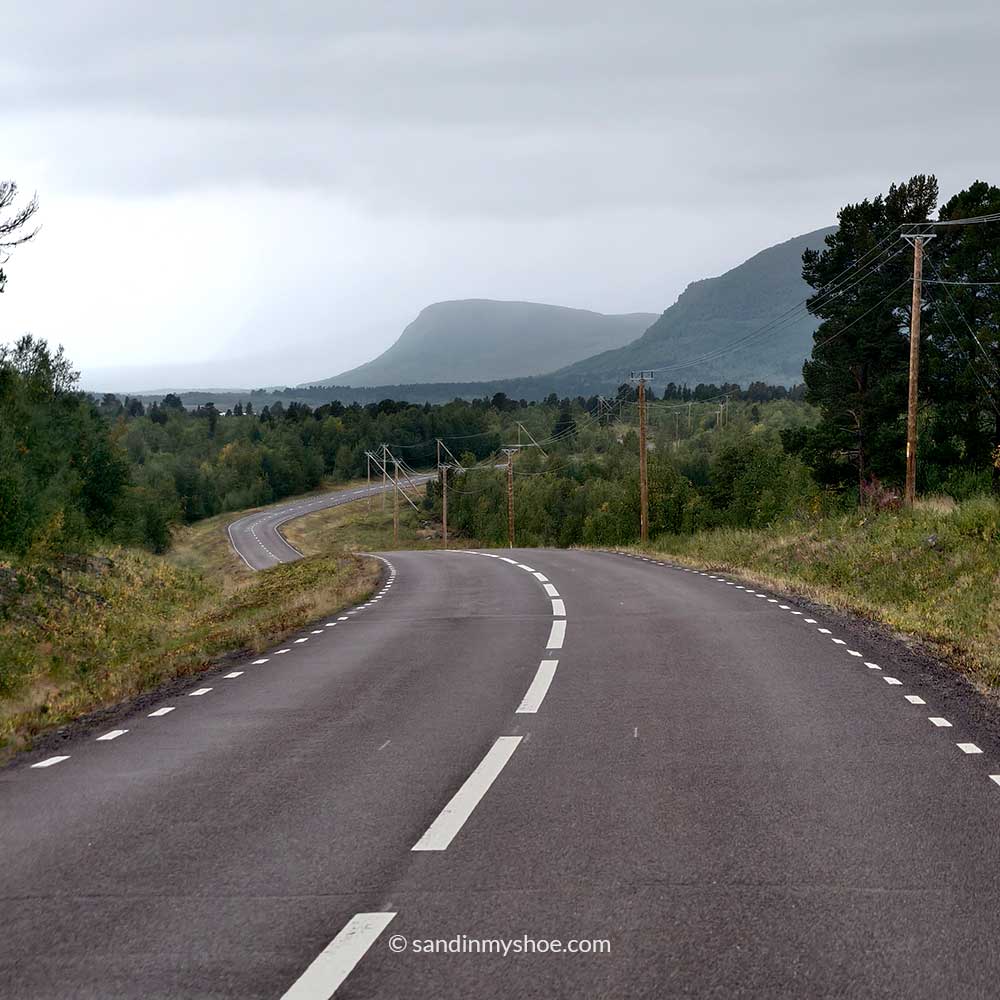

The road was busy with mining trucks at first, but they disappeared about halfway to Nikkaluokta. From there, it was just me and the open road, with only the occasional passing car or camper. I stopped along the way to cook and dry the clothes that had been damp since Gällivare—a few days earlier. The smell of sausage frying filled the air as I hung my clothes to dry in the sun. Once back on the bike, the smooth asphalt and empty road let me finally settle into a rhythm, riding freely as the horizon filled with mountains and rivers.

Arriving to Nikkaloukta

Just before reaching the camping grounds in Nikkaloukta, I pedaled through open tundra, the low vegetation stretching endlessly in every direction. I crossed a bridge over glacial water that shimmered green in the sunlight, its icy clarity reflecting the vast sky above. The landscape had transformed—crisp, fresh air filled my lungs, and the silence of the tundra was almost tangible. It felt incredible to finally arrive, but I knew the toughest physical challenge was still ahead.

Reflections on week 3

By the third week—plus two extra days—I had finally reached the starting point of the trek: Nikkaluokta. I had really enjoyed cycling and spending quiet camping nights in the most remote areas surrounded by beautiful nature and reindeer, and experiencing the quirky habits of the northerners.

Continue Reading

The next day, I would hike 20 kilometers carrying roughly 15 kilograms of gear: food for several days, water, clothes, a sleeping bag, and my tent. Each step would demand everything I had, because I was already exhausted.

No comments yet, be the first one!

I appreciate hearing from you. If you have any suggestions, questions, or feedback, please leave a comment below. Your input helps ensure the information stays relevant and up to date for everyone.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts!